This is an important question, because it shapes much of what we believe about the end times, about what our current relations with the modern nation-state of Israel ought to be like, and, most importantly, about the centrality of the Church to God’s plan. The classic Christian position on this question was that God’s plan had one single trajectory: all of God’s covenants (with Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and ethnic Israel, etc.) were fulfilled in Christ and his church. In the 1800s, however, a theologian from the Plymouth Brethren began popularizing the second answer as a possibility: that ethnic Jews, as God’s “chosen people,” are still heirs of their own separate covenant from God, and that some of the promises in the Old Testament aimed specifically at them are yet to be fulfilled. Jesus Christ is the Jewish Messiah and is the fulfillment of some elements of their covenant, but the Church is actually something different—it is a sort of parenthesis in God’s plan for Israel, aimed specifically at bringing as many of the Gentiles as possible into God’s covenant-kingdom before the final fulfillment of his covenant with Israel at Christ’s return. This answer, known as Dispensationalism, became wildly popular among American evangelicals (thanks to the advocacy of D. L. Moody, the Scofield Bible, Dallas Theological Seminary, and a host of premillennialist end-times teachers), and remains so to this day.

The Rise of Dispensationalism

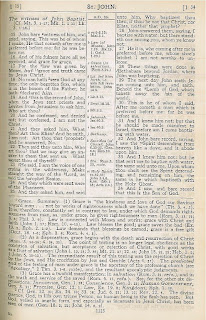

In the 1830s, an Irish clergyman named John Nelson Darby (pictured above) became one of the founders of the Plymouth Brethren and began expounding his idea that Israel and the Church constitute two separate peoples of God, with separate covenants and separate fulfillments. Dispensationalism views history as divided into a series of covenants between God and humanity—the most basic view has three separate covenantal periods: the Mosaic covenant, the Church covenant, and the final Kingdom Covenant when Christ returns (more complex schemes also include covenantal periods for Adam, Noah, and Abraham). In the Dispensational scheme, however, the Mosaic covenant is not superseded or fulfilled in the Church covenant—the two operate side-by-side throughout the present age, both linked to Christ and to the separate fulfillments he will grant to both at his second coming.

New Testament Teaching on Israel and the Church

|

| Scofield Reference Bible |

Attitudes toward Israel in the Early and Medieval Church

Unfortunately, many people in the early and medieval church were blinded by racial prejudice, and forgot Paul’s teaching about Israel. They came to hold a belief known as “supersessionism”—the idea that the church did not fulfill God’s covenant with Israel, it replaced that covenant. Christians in these eras believed that because many Jews had rejected Jesus as their Messiah, God rejected them and replaced them with the church. This idea is not well-founded biblically, and has since been rejected by theologians of almost every branch of Christianity.

The Reformation – Israel in John Calvin’s “Covenant Theology”

The Protestant Reformers, most notably John Calvin, helped to recapture the biblical sense of the fulfillment of covenants. Though he (like the Dispensationalists) divided biblical history into periods marked by God’s covenants with humanity, he saw Christ and the church as the fulfillment of all previous covenants. God’s plan for all people, from all time, has been the church of Jesus Christ. (It’s important to note, however, that the fulfillment of all the biblical promises includes what the church will be at the end of time, not merely what the church is right now.)

Israel and the End Times

This issue plays into the variety of beliefs about the end times. Dispensationalists believe that at Christ’s Second Coming, all the remaining promises to Israel will be fulfilled physically and literally in his reign as the Messianic King in Jerusalem throughout a 1000-year “millennium,” often including a rebuilt Temple (this position is part of the end-times system known as dispensational premillennialism). Non-Dispensationalists, however, either view the millennium as the reign of Christ and the church rather than as a specifically Jewish-focused part of God’s plan (historic premillennialism, postmillennialism) or as a symbolic description of the current church age (amillennialism).

What about the Nation of Israel?

If the Dispensationalists are correct, and the Jews continue to have an ethnic/national future fulfillment guaranteed to them in God’s plan, then Christians ought to be supportive of the current nation-state of Israel in any and every way we can. If, however, the classic Christian position is correct, then, while we honor Jews as our older brothers in the faith of Abraham, we do not need to treat Israel as being in a special class among the nations, because God’s plan does not hold a specifically ethnic/national future for them—rather, their future would be the church of Jesus Christ itself, which is not something foreign to them, but their own ancestral patrimony. The position of Israel, nonetheless, is one of special honor and affection in both views.