Question: Who makes the decision about what you can believe? Does a believer’s family, or their church, or society as a whole, properly define their beliefs? Or should each individual believer have authority to make their own decisions about what they believe?

The answer to this question may seem obvious to us, but that’s just an indication of how deeply Baptist influence has become a part of Christian practice, especially here in America. “Everybody should be able to decide for themselves what they will believe”—this is a peculiarly American statement culture-wise, and a peculiarly Baptist statement theology-wise. By the time the Baptists emerged in the 17th century, many Christians never really made the act of choosing to believe anything for themselves. They would be born into a Christian family and a Christian nation, and they would be baptized and confirmed as a Christian, and then they would be taught what they ought to believe from their bishops, priests, and catechists. There was very little freedom for the individual Christian to look through a Bible for himself and decide on that basis whether he would believe or not believe the doctrines presented to him by the church.

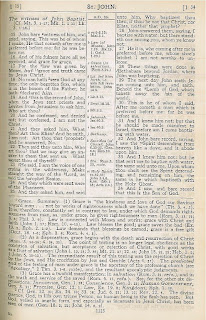

Freedom of the Individual – The early Baptists, emerging from a Puritan/Anglican background, were passionate about reading the Bible for themselves. What they discovered in the pages of the New Testament was the idea that every person was accountable for himself alone (Rom. 14:10-12) and that the call of faith to the world was a call for individual belief (John 3:16) instead of social affiliation.

- Baptism – Because salvation is understood as a matter of individual belief, then a believer’s choice becomes the crucial element. In much of the traditional Christianity of the Catholics and Anglicans, believers would not choose their own belief; they would be baptized as babies on the choice of their parents. Baptists, following the example of the Anabaptists of Holland, did away with the practice of infant baptism. If baptism is the symbol of one’s coming to faith, then it could only be accomplished after that person was old enough to consciously decide to believe in Christ for himself or herself.

- The Importance of a Pious Life – Baptists also emphasized the importance of a pious life. If your choice for Christ is a crucial element in your salvation, then that choice has to be manifest in every area of your life. It wasn’t enough anymore to think that the power of the sacraments would save you, as long as you received communion and went to confession—no, real faith was chosen faith, and that choice needed to be shown in every part of your life. If you weren’t at least trying to live a pious life, then there was question as to whether you were really a Christian at all, and you couldn’t be a member of a Baptist church. Baptist churches, unlike the Anglican parishes around them, included only those people who were visibly laboring to live a Christian life.

Freedom of the Local Church - Every church is “the Church” – While they were reading their Bibles, Baptists came to the startling realization that in the New Testament, each local church was treated as a manifestation of the whole church. Each local church, whether in Corinth or Philippi or Ephesus, was “the Body of Christ.” The Apostle Paul assumed that all of the necessary spiritual gifts and all of the necessary ministries of the Church would be present in each local body of believers. This means that each local church had the authority to read Scripture, teach theology, and practice ministry within its own capacities, without leaning on any outside churches.

- No Hierarchy of Offices – Because of this biblical fact, Baptists did away with the stratified hierarchy that had developed in the Roman Catholic and Anglican churches. There would be no more popes, cardinals, or archbishops—there would simply be the church officers listed in the New Testament—deacons/elders, and overseers/pastors. The people filling these offices were gifted for ministry and service, but would have no more authority than the ordinary layman, because the ministry of the Holy Spirit in the church, speaking to every person, meant that no one was considered to be closer to God than anyone else—we are all “a kingdom of priests.”

- Separation of Church and State – Baptist churches also proclaimed their independence from the state. Most traditional churches were “established,” national churches, and the intersection of faith and political power had often turned the church into an unspiritual puppet of the government. Since no one could decide for an individual what they ought to believe other than the individual themselves, the same principle applied to churches—no outside government could impose beliefs or practices on the church. Thus Baptists were the early champions of “the separation of church and state.”

- Voluntary Associations – Even though Baptist churches were independent in authority, they made it a priority from the very beginning to maintain close partnerships with other Baptist churches. The biblical principles for this are clear, and the dangers of being a purely independent church so great, that it became a core element of the Baptist tradition. Without joining voluntary associations, “independent Baptist” churches become far less accountable to their brothers and sisters in Christ, far more isolated in ministry and mutual support, and far more prone to veer off into theological errors from the influence of a disconnected pastor or leader.

Conclusion: Baptist theology changed the world. Our once-radical idea, that everybody should be able to decide for themselves what they believe, is now commonplace.