Discerning the Intended

Goals of Adoniram Judson’s Burma Mission

Although a record of goals

for the Judsons’ Burma mission was never set down in their writings, it is

possible, by looking at the course of actions which they undertook, to discern

a tentative list of ministry priorities. Those goals that were undertaken

earliest, most frequently, and to which the most time was devoted, ought to be

considered the top aims of the Burma mission. The overriding priority, above

all others, was the salvation of people who had never yet had the opportunity

to convert to the Gospel of Jesus Christ. However, Adoniram himself recognized

two distinct goals under this aim: the Burman “department” of the mission, and

the Karen “department.” The goals listed below will follow this separation.

First, the primary goal of

the Judsons’ mission was the conversion of the Burmese people (that is, the

Bamar). These were the residents of the Irrawaddy River valley, whose

civilization was ancient, sophisticated, and widely respected. They were

politically organized under a king with an efficient regional system of

administration, were homogeneously Buddhist in religion, and all spoke the

Burmese language. This was the people group to whom Judson intended to bring

the message of Jesus Christ from the very beginning, upon reading a book about

“the Golden Kingdom” of Burma as a young seminary student, and he and Ann often

expressed confidence that they would see “that these idol temples will be

demolished [in Rangoon], and temples for the worship of the living God erected

in their stead.” Like all missionaries, their goal was to win enough converts

and to train them well enough that, once Adoniram and Ann’s missionary service

was done, the fledgling Burmese church would continue to exist, to grow, even

to thrive, under the leadership of native pastors.

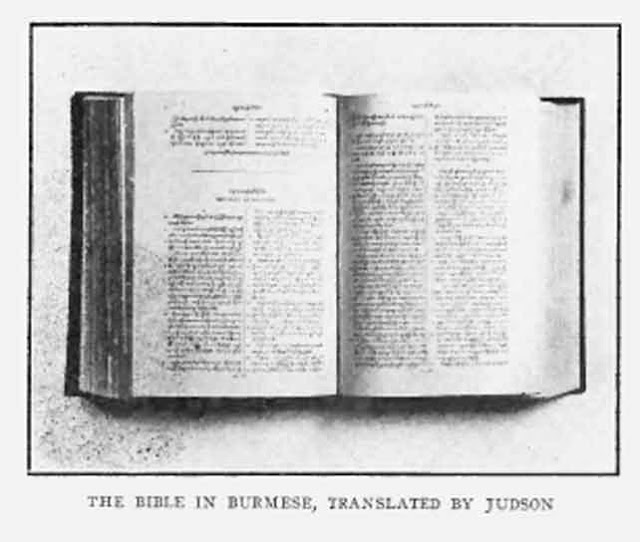

The second goal of the

Judsons’ mission, and one of the great means by which they hoped to accomplish

the first goal, was the translation of the Bible into the Burmese language.

This project was undertaken by Adoniram as soon as he had achieved the most

basic, requisite level of fluency, and it continued through almost his entire

ministry career. In several seasons of his ministry service, the translation

project was his sole pursuit. The difficulty of this endeavor cannot be

overstated: in an age before the science of linguistics emerged, and without

the modern helps for language learning, Adoniram Judson mastered one of the

most complicated languages in the world, and translated the Bible into it

directly from Greek and Hebrew. Further, he advocated for Bible translation as

a necessary and paramount pursuit in missiological practice, thus shaping the

developing Protestant missionary tradition.

The third goal of the Judsons’

mission team, which appeared only when the opportunity arose for it, was the

push to convert the non-Burmese tribes of the mountainous interior. This

venture began only after more than a decade of long, difficult work in trying

to attract a precious few Bamar converts to the Gospel. While it was never

explicitly expressed as a lesser goal, it was undertaken only after the chance

to pursue it fell into their laps, with the conversion of Karen man who had

been sold into slavery in Moulmein and who thereafter became passionate for the

evangelization of his people.

There were, of course,

many smaller aims which occupied the labors of the mission team, most of them

tangentially related to the ones stated above, such as Adoniram’s further

linguistic endeavors, Ann Judson’s work in opening a small school for Burmese

women, and Dr. Price’s medical missions work, but they tended to be individual

goals of team members rather than overriding goals of the mission team itself.

Success of the Burma

Mission’s Intended Goals

As regards the first goal

of Adoniram Judson’s Burma mission, an objective observer would be forced to

conclude that it had largely failed. That assessment is made from the practical

results of his work, as compared with his initial hopes and expectations. It is

not to say that the labors he put into pursuing that goal were fruitless, nor

even that they could have been better expended elsewhere. Judson and his team

did succeed in baptizing at least a hundred Bamar Christians during his

ministry (most of that number being converts who joined his church in the later

stages of his ministry, while under tolerant British rule in Moulmein), and

Christian theology teaches that the soul of even one single convert is a

priceless treasure at which heaven rejoices. In that specifically theological

sense, then, Adoniram’s work with the Bamar was a success—the Kingdom of Christ

gained its first-ever Bamar disciples thanks to Judson’s work. When the Colmans

inquired what the chances of “ultimate success” for the mission were, Adoniram

wisely replied, “As much as that there is an Almighty and faithful God, who

will perform his promises, and no more.”

However, when assessed in

the light of Adoniram’s own expectations, the response of the Bamar people to

the Gospel was not what he had hoped. He described the effort required to gain

one convert as being “like drawing the eye-tooth of a live tiger.” Many of his

early converts were scattered in the war, and he never found out if they had

retained their faith. Most of his trips to Ava and Rangoon ended with a bitter

sense of that society’s hardness to the Gospel. Even his sizeable congregation

at Moulmein often left him with doubts as to the congregants’ commitment to the

faith. Today, more than two hundred years after the Judsons began their labors

in Rangoon, the Bamar people are less than 0.1% Christian (numbering about

5,000), though that tenth of a percent remains a testimony to the continuance

of their work.

In assessing the second

goal, the translation of the Bible into Burmese, one would have to say that it

was an overwhelming success. Adoniram’s Burmese Bible, translated and revised

over a period of nearly four decades, was a testament to his linguistic skill,

devoted faith, and love of the Burman people. Perhaps more than any other

effort he made, the translation of the Burmese Bible assured the ongoing

existence of a remnant of Bamar Christians through the generations to come. The

quality of this translation was so good that it remains in widespread use to

this day: though newer translations with updated language are now available,

many Burmese Christians have reverently clung to the Judson Bible as their

“King James Version” into the twentieth century and beyond.

The third goal, that of

bringing Christ to the minority people groups of Burma, was an extraordinary

success. It may have been something of afterthought to Adoniram himself, but

the evangelization of the Karens (and later the Kachins) left an indelible

Christian mark on the whole of Burmese society. The Karens in particular were

uniquely suited for Christian evangelization. They had an ancient

origins-legend which told them that a great Creator-God, Y’wa, had made three

races of people (Karens, Burmese, and a lost, light-skinned brother race). Y’wa

had entrusted them all with a sacred book teaching them his ways, but the elder

two races lost their copies. They retained the hope, though, that one day their

lost, light-skinned younger brothers would find them again, and return to them

the book of Y’wa. So when two white missionaries from Maine, George and Sarah

Boardman, bearing a sacred book from the Creator-God, appeared in the Karens’

villages in the late 1820s, the response was enormous. The Karen came to Christ

in enthusiastic waves, pushing the population of the Christian community in

Burma up to at least 10,000 by 1850, and perhaps high as 30,000. Despite the

paucity of Christian belief among the Bamar, the extent of it among the Karens

is so great that Myanmar (Burma) stands today as one of the top ten Baptist

nations in the world, numbering nearly a million members (and thus exceeding

the entire Baptist population on the continent of Europe, where the denomination

began).

Unintended Successes

There are two other major

successes of the Judson mission team’s ministry that are worth mentioning,

though they never seem to have crossed the Judsons’ minds as intended goals at

any stage in their missionary careers. First, they managed to give the

incentive for two different Protestant denominations in America to develop the

infrastructure, passion, and financial networking for overseas mission efforts.

The Judsons’ enthusiastic drive to become missionaries to Burma was a major

part of the raison d’être for the development of the Congregationalists’

mission arm, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, which

would go on to be a major player in the “golden age of Protestant missions.”

Further, by converting to the Baptist denomination and sending Luther Rice back

home to advocate on their behalf, they also succeeded in giving the Baptists in

America an incentive to organize themselves into a mission society (known as

the Triennial Convention), which commissioned nearly one hundred missionaries

in just its first two decades. James Knowles, Judson’s contemporary and the

pastor of the Second Baptist Church of Boston, notes that Judson’s conversion

“resulted in…the formation of the Baptist General Convention in the United

States.” Richard Furman, a pastor from South Carolina, also attributed the

formation of the Baptist Triennial Convention to the recently-awakened concern

for “the millions upon whom the light of evangelic truth has never shone.”

Second, the celebrity

status that the members of the Judsons’ mission team earned back in America had

impressive results. Not just Adoniram and Ann, but many peripheral members of

the team as well (the Newells, the Colmans, and the Boardmans in particular)

were remembered as missionary-martyrs, and their acts were read about in a

series of books that all became American bestsellers. Joan Jacobs Brumberg

notes, “No nineteenth century American family was so closely tied in the public

mind to the cause of evangelical Christianity.” By the time Adoniram returned

to America in 1845, he discovered that he was one of the most famous men in the

entire nation, and that a whole generation of babies had been named after him.

Even within his mission service in Burma, the Judsons saw the fruits of this

influence in the many new missionary couples that joined their team over the

years, almost all of them inspired by stories of the Judsons themselves. It

would be no exaggeration to say that the Judsons’ example was one of the

leading forces that launched an entire generation of American missionaries.

Conclusion

Adoniram Judson, his

wives, and his other mission team members, accomplished tremendous things

through their persistent labors for the Gospel of Jesus Christ. It stands as

one of the ironies of the Judson legacy that their primary goal, the conversion

of the Bamar people to Christianity, was never realized (at least not even

close to the extent that Adoniram hoped). Nonetheless, the Judsons’ mission

team succeeded in bringing the light of Christ to the Golden Kingdom of Burma,

and attained such monumental successes in their other labors that their legacy

rests secure as one of the greatest teams of missionaries in the annals of

Christianity.